We are so fond of one another

because our ailments are the same.

Jonathon Swift (Journal to Stella)

Cecil Graham: What is a cynic?

Lord Darlington: A man who knows

the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Bernard Shaw (Lady Windermere’s Fan)

The Pendulum of Common Sense

- Why and when we may be unrecognisable

- Value and significance: similarities and differences

- The limits of conscious control

Insoluble problems

Some things are important, others less so, whilst others are totally insignificant. How you hold a cigarette, for example, belongs to the last category although, as far as fire-safety is concerned, even this may sometimes be significant.

The desk I am writing at now has two values: a shop price, and a special price (as a family heirloom) which cannot be expressed in monetary terms, that is to say, the desk is of significance to me; or, to put it another way, it occupies a place in my hierarchy of personal values.

Terms like «system of values», «scale of values», «value games» and «value orientation» are met frequently in philosophical, sociological, psychological and mathematical studies. Physiology and psychiatry are also concerned with significance and value.

A question:

Whose life do you value most: your father’s, your mother’s, your child’s or your own? Imagine your house is on fire, whom would you save first?

«...What about your parents? After all, you may have several children but only one father and mother».

«Now, come off it, you can’t go making cold-blooded calculations about things like that!»

Quite right. It is impossible to know in advance how you would react in a similar situation. You have to wait until you are forced into making a decision and then there is nothing for it but to rely on your subconscious. To most parents, the life of their child, to most children, the life of their parents, and to most people, their own life are all things of super significance. When any of them are seriously threatened various defence mechanisms are set in motion: we involuntarily ignore the cause of our anxiety, we push it to the back of our mind, forget about it, or simply lose consciousness, faint, etc. This, of course, is the ostrich’s technique of burying its head in the sand and it is the ‘solution’ we often use for insoluble problems. This is what women do to forget about the pain facing them in child-birth, what we all do to things which remind us of death, illness, war, disabilities, our debts, our conscience, the times we have let people down and been let down, sharp knocks to our pride, and so on. There are thousands of situations in which we exercise this capacity to ignore and forget, although we are never entirely successful. Gambling with Life as the stakes is evolution’s major occupation. It is the Game of Games for each of us and it is therefore quite understandable why it takes place at a fundamentally subconscious level. The two-edged advantage of being able to engage in rational thought can easily be outweighed by the tempting simplicity of trusting to instinct alone if there is nothing of particular super significance in our lives. The things which are of real significance for us generally escape our scrutiny and slip off into the shadows: it is doubtful whether we ever know what they really are.

Trivialities’ Tricks

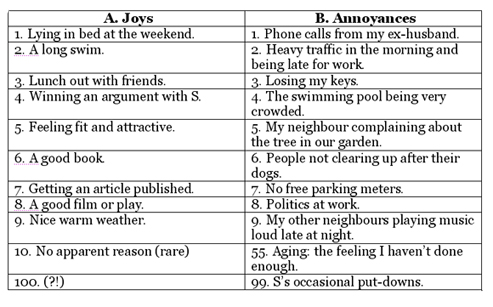

Ms. K., an extremely pleasant woman with an M.A. in philosophy volunteered to complete two questionnaires.

The first was headed:

«The hierarchy of your values in descending order».

Ms. K. wrote:

1. To feel I’m needed, that I’m useful to the people close to me, to society, and to humanity as a whole.

2. Good health.

3. To love, be loved and to be happy with my family.

4. To have interesting and demanding work.

5. To continue to learn and to widen my intellectual horizons.

6. Friends and meeting people, good relations at work and at home.

7. No money worries.

8. To get away at weekends.

18. To be able to go swimming several times a week.

55. S’s approval.

71. To be sexually attractive.

80. A tidy house.

100. Getting to work on time, little traffic.

The second questionaire was entitled:

«Things which bring you joy or cause you annoyance. In descending order of intensity».

A. What pleases you most of all and enables you to be in a good mood?

B. What annoys or depresses you and enables you to be in a bad mood?

The results were as follows:

If you compare the relative points on the two questionnaires you will find that our abstract hierarchy of values does not always tally with the feelings we attach to real events. Things of greater and lesser importance are mixed up, sometimes apparently quite randomly; at times they even seem to contradict or simply to discount our hierarchy of values. This happens to me, and perhaps to you, too. Why? Why do we often seem to treat events of major importance with a strange indifference, whilst we overreact to mere trifles?

At this point we should define our terms more exactly: is value the same as significance? Common sense would appear to suggest that they are identical but, as we are well aware, we are not directed by common sense the whole time: we are also influenced by bio-pendulums which have their own special functions.

Day and Night

The diagram (2) shows the most important pendulum, the range of tone, or our activity pendulum. I shall refer to this diagram again since it illustrates the basic range of all our bio-pendulums, including the range of our relationships and mood: our emotional pendulum.

Diagram 2.

The Activity Pendulum.

Many benefits of Auto-Training are gained by regulating this pendulum. Of course, life is much more complex than the diagram. The activity pendulum, the fly-wheel in the machinery of living, has a basic daily rhythm moving between asleep and arousal. However, its swing is additionally affected by our food intake, the weather, what we are doing, our mood and the composition of our blood, etc. There are also extreme states (forbidden or reserve zones only reached in rare, even pathological conditions): paroxysms and fits at one extreme, and complete insensitivity, shock and coma at the other.

Just how difficult it is to draw a general picture is all too clear once we understand that all our pendulums are interconnected and interdependent. We often instinctively realise that it is advisable to make allowances for other people’s activity and tone pendulums, especially if we have some important dealings with them. For example, if Mr. T. has to ask his Bank Manager for a bridging loan for his new house, he will be desperately hoping to find a relaxed and smiling Ms. B. waiting for him, that is, a Ms. B. who:

1. has had a good night’s sleep;

2. is on excellent terms with her husband;

3. has just had a healthy and sustaining lunch;

4. is not being troubled with her recent running injury;

5. etc.

If this is the case, Mr. T’s approach will be correspondingly bold and assured and he is likely to be successful.

Things, however, could be quite different. Suppose, say, that Ms. B. did not get a wink of sleep because the new neighbours were having a party till the early hours, when the cats of the neighbourhood conspired to chorus in the dawn. Mr. T. would then be facing a much more formidable problem in the person of a less accommodating Ms. B. If the latter had also had a row with her husband over who should complain to the neighbours and had not yet had lunch, Mr. T. would be well advised to beat a hasty retreat and make another appointment at a later date.

Unfortunately, however, we are less willing to acknowledge that we ourselves and the people close to us are equally affected by these bio-pendulums and by our physical state in general.

Let us turn our attention to the central point on the pendulum’s swing, the point between arousal and rest. This is the position of balance which is not always that easy to attain but which we shall assume is the point of concentration you have reached whilst reading this. What is now preventing you from closing your eyes and drifting peacefully off to sleep? I am fairly sure it is not the book. To fall asleep you would in fact have to pass through a number of intermediary stages. Both arousal and rest are the result of only a very slight oscillation of the activity pendulum within the limits of normal waking life which is under the control both of our conscious will and external circumstances. From a state of rest you can easily slip into relaxation; once relaxed, you can quickly fall into a state of drowsiness. If you are neither tired, ill, or upset, a state of arousal changes into one of excitement almost of its own accord.

(You may well be thinking this is all rather obvious, but the whole point is that for many people even basic things like relaxation and concentration require considerable effort.)

To progress further, however, is much more difficult. Inertia affects the pendulum in two ways: whilst it is still in the central region, inertia makes it difficult to move to an extreme position; however, it is equally hard to stop the process once it has started moving to either extreme. If you are dropping from exhaustion but are still managing to keep going simply because you have to, you only have to get really comfortable and you will be sure to nod off in no time at all. Similarly, if you are very tense but are still keeping reasonable control, someone just has to say one wrong word and you will either flare up angrily or burst into tears. It is then very hard to return to your former state and all you can do is wait for the reaction to run its course, unless you curtail it artificially (with tranquilisers, say). You are incapable of helping yourself when you are fast asleep, in a rage, in a panic, or in deep despair, are passionately in love, or having a fit.

Our bio-pendulums work approximately and continue to function by inertia. They are clumsy and indirect and are consequently unable to keep up with the swiftly changing, subtle demands we make on ourselves consciously, although these may not always cope with the pace of events either. If, in the course of our everyday lives, one of our bio-pendulums (that of our emotions, for example) swings into an area outside our conscious control, our hierarchy of values becomes confused. What is it that makes a forty-year-old act his age in the street and the library, for example, whereas at work he appears young and inexperienced, with his wife he behaves like a teenager, with his children he is a stubborn and stupid child and at the least cold or headache he is immediately a helpless baby? Why is it that, in making collective decisions, we are often willing to be sheep, whereas in a fight for survival we turn into lions, wolves, rabbits and various other predators and prey? What happens to all the values we claim to profess?

The most likely explanation is that they are smothered by something which is fleeting, though at that particular moment of overriding significance as our pendulums swing out of the sphere of conscious control. Consequently, it would seem that value and significance are, essentially, quite different, although closely linked. However subjective the value of a thing may be we can attempt to compare it with other things, describe it and estimate its true worth, (even if we only do so in retrospect, when we have already lost it). But as soon as we try to express the significance something has for us we have to resort to gestures and interjections.

We can, therefore, define significance as a subconscious evaluation of something, and value as significance we have become conscious of. In fact, we measure our inner values in the same way as we measure general ones, that is, by comparing the concept or object in question with something which has a universally accepted value: «Health is more precious than gold»; « I value my freedom more than my than life». Significance, however, can only be measured in terms of our state of mind, since it is the sum of all our judgements concerning significance which ultimately determines our state of mind. We use words to express the value we attach to something, whereas its significance is conveyed by our intonation. You probably think that a bootlace is of little value to you, but if it happens to snap just as you are racing to catch a train then, although its value remains constant, its significance is suddenly quite different. A glass of water may have little value but its significance is considerable if you are stranded without water in the desert.

Anyone whose hierarchy of values coincides with that of personal significance is harmonious and sincere, with him or herself at least: a marked discrepancy between value and significance leads to disharmony, a split between the heart and the head. This is a conflict we come across daily and, when mild, we accept it as normal; only in its extreme, overt forms is it considered pathological. «Painful insensitivity» is a well-known psychiatric condition. People experiencing this complain of an inability to experience emotions of any kind: they are totally indifferent to everything and the whole world seems empty and grey. At the same time, however, they torment and hate themselves because of this condition; they accuse themselves of being cold and heartless. Their faculties for assessing significance have clearly ceased functioning, whilst their sense of value remains and leads to the endless self-recriminations. The opposite condition, a ferment of unattached significance, also exists and is manifested by vacuous excitement, aimless hatred, unprovoked sadness and ecstasy and even love for the world in general but no one in particular. This is all the work of our bio-pendulums swinging to and fro. The sound advice «to leave someone alone to cool down for a bit» intuitively presuppose that, if left alone, unattached significance will have no difficulty in finding something to latch on to.

It is when that which is of significance to us is in harmony with our values that we are able to act as mature human beings. Unfortunately, our instincts and physiology set significances of the moment against our deeper inner vlaues. Our actions are only likely to be rational when they fall within the relatively narrow zone around the central point of the pendulum’s swing where value changes into significance and/or our mood and physical state. As we approach either extreme of the pendulum’s range, however, the opposite is increasingly apparent, and things which are of significance to us become our values, and our mood holds sway over our judgements. People who are carried away (in the heat of an argument, perhaps, by love or an addiction) are aware at times that they are not saying, doing or feeling things in the way they should, and yet they continue as before, not in spite of, but even because of this awareness.

You may well be wondering where this rather involved discussion is leading. The point is that:

Auto-Training enables us to harmonise those things that are of significance with those that are of value to us.

In Black and White

When we write things down we can use familiar terms to divide personal values and their corresponding significance into arbitrary categories without much difficulty.

This is all fairly straightforward and there is no particular need to remember it. The important thing is to understand or, to be more exact, to take another look at a few simple and fairly obvious facts. Namely that:

• the pendulum’s two extremes are far apart: there is a long way between «all» and «nothing»;

• although you might expect it to be boring in the central zone it has compensations that people of the extremes can never appreciate;

• experiences of all kinds can be used for personal development.

A Puzzle

There is a Russian fairy tale about an old man and his wife who have a hen which lays a golden egg. But their good fortune is short-lived since a mouse runs past and knocks the egg with its tail. The egg falls and shatters; the old couple mourn the loss of their precious egg. However, the hen tells them to cheer up since she will lay them an ordinary one in its place. The old couple accept the egg and happily get on with their lives.

Considering this in terms of significance and value, we can see that when we have something of super significance (the golden egg is a symbol of super value (4)) then we are vulnerable to upset, depression, grief, etc. if we lose it. You could say, our emotional pendulum swings from the positive zone into the negative, from ‘heaven’ into hell’.

Diagram 3. The hierarchy of values and inner significance.

The hen in the tale at first acts as temptress, offering an object of super significance, the potential source of neurosis. She soon thinks better of this, however, and changes to the role of psychotherapist, offering something of medium significance in its place on the understanding that an ordinary egg in the hand is worth two golden ones in the bush.

Is it ever possible to identify super-value or its subconscious form, super-significance?

It is, but only in other people or in ourselves retrospectively, that is, when our values have already changed.

Clarifying Terms

• Inner value is the degree of dependence we decide we are going to put on something or someone, including ourselves.

• Inner significance is the degree of dependence we actually feel.

It is very important to realise that here we are considering purely subjective attitudes and dependencies since objective ones may be quite different. A diabetic, for example, may feel that she is so annoyed because of something her husband or children have done or just because the post is late whereas, in fact, it is simply due to her blood sugar level. In other words, we are dealing with illusions which are nonetheless linked to reality and form the basis of our inner life.

When we subsequently start the course of Auto-Training itself, we will scarcely mention the terms «value» and «significance» as such although, essentially, we are concerned with them the whole time. Initially, however, it is important to distinguish clearly between what is of value and what is of significance for you, or there is little point in attempting to go on with Auto-Training. It can be useful to fill out a questionnaire on the lines of Ms. K’s earlier in the chapter since this will help you to sort out the ideas you have about yourself, and may even hold a few surprises.

A Complex Unity

We would probably be fairly sceptical about claims of a wonder cure that could work equally well for cancer, boils, alcoholism or unrequited love, although the more specialised the treatment and the more idiosyncratic the ailment (the answer to insomnia caused by too much T.V., say, or to impotence caused by eating pickled onions), the more open-minded we might tend to be.

Despite our justified mistrust of panaceas, however, most of us would probably hope deep down that «it might just work this time». This is not just a product of our insatiable capacity for wishful thinking: there is some reason to think this way.

Ailments come in different forms, some are localised (a hernia, for example), whilst others (an allergy, say) are more general in their effect. Treatments can likewise have a narrow or wide sphere of action, although there is nothing which either cures all or affects only one part of our bodies. There are countless illnesses and problems but human nature is a coherent whole. Unlike machines, which are assembled from components brought from various parts of the world, we are born ‘ready-made’ and simply develop in the course of our lives. Although we are nevertheless composed of numerous components, we have only a few universal mechanisms controlling and coordinating them: if this basic machinery is functioning well there are no problems; if it is faulty in any way then...

It was only after considerable practical experience and thought that I realised that, although there is a wide range of neurotic states and psychological problems, they are all essentially linked to our bio-pendulums. I then understood that disorders which apparently have little in common (for example, obsessions, stuttering, insomnia, impotence, anorexia nervosa, etc.) are, in fact, simply manifestations of the same paradox of super-significance; also that numerous conflicts, both internal and external, have fundamentally similar causes. The obvious conclusion from this was that the way to help these states was to find either one universal cure or, more realistically, a selection of different ones which would act in the same general direction.

A number of studies approaching the problem from various points of view and expressed in different terms have led to essentially similar results and my idea in no way challenges the validity of other interpretations, for example, those based on psychoanalysis or socio-psychology. Nevertheless, I feel mine is a convenient explanation of internal human processes that can be of use to non-professionals. A genuine psychological recovery is possible only if we are willing to cooperate with it and if we have even an approximate understanding of our state and treatment. If psychotherapy is, therefore, to be of any real use then, apart from anything else, it should include at least some basic instructions in psychology.

The Paradox of Supersignificance

This occurs, for example:

• when we come close to dying or when our health is seriously threatened, even if only temporarily;

• when we are jealous;

• in exams and vivas, and whenever we have to speak, read or sing, etc. in front of someone whose opinion we consider important;

• when our pride or our self-esteem are threatened;

• every time an obstacle arises just as we are about to achieve something we have been aiming at for a long time; whenever there is a hitch in the smooth running of things: for example, when a train is announced to be running forty-five minutes late;

• whenever we are really pushed for time;

• in any conflict, scene or quarrel, particularly between people who love each other, and so on.

These paradoxical conditions are the "beam" which was discussed in the last chapter and which we will come across again subsequently.

The pendulum’s course is quite clear: the further it swings in one direction the further it is potentially able to swing back in the other. The activity pendulum moves from a tense state of arousal into a deep sleep (in a healthy person), from a fit into a deep coma (in an epileptic). Our emotional pendulum moves from «Hell” to «Heaven” (hot, irritable and parched with thirst, you sit down to have a long, cool drink) and back again (a drug addict’s fix wears off, for example). Understanding this, it is easy to see how blissful tranquility can dissolve into hysteria, why melancholy can follow jubilation like a shadow, and why new joys bring new anxieties. (The pleasure of purchasing a car, for example, may be clouded by worries of maintenance and running costs, etc.). It is all vicious circles within vicious circles, as eastern philosophers who advocated the extinction of desire as the means of attaining peace of mind understood a long ago.

Our scale of personal values may be seen as a nail from which the pendulum of significance hangs, swinging to and fro. These natural oscillations affect our way of thinking at all times and an understanding of them helps us to foresee some things and to control others. If, for example, someone makes it obvious that he or she is ignoring you, then they may well be interested in getting to know you better. (This can be fairly plain, it is true, even if you do not know anything about your bio-pendulums!) But it is not so easy to appreciate that we may at some point despise the person we are infatuated with at the moment. You should not be surprised if the epitome of a perfect gentleman sitting next to you at dinner turns out to be an ill-mannered lout once he has left the restaurant and especially, perhaps, when he is at home. This is as natural as a drunk’s caprices when he slaps you amicably on the back one minute and punches you on the nose the next. It may well be that someone who is overtly servile is also sadistic; if someone is inclined to make quiet, sarcastic remarks, then they may be irritable or easily embarrassed since the pendulum tends to swing from one level of significance on one side to its counterpart on the other. In conversations we are generally affected by the level of significance the person we are talking to adopts, answering either with the same (frankness for frankness, an easy manner for an easy manner), or with the opposite kind of significance (boisterousness with apathy, say, or adulation with contempt). The greater the significance for the person we are with, the more extreme our positive or negative reaction will be. But we should not forget that some values and significances are not genuine, existing purely for show, and that what we express is often the exact opposite of what we really feel. This duality can be more pronounced the more sophisticated our thinking. People who never show any extreme reactions are often seething with bottled-up emotion which may erupt one day or, as is more often the case, will continue to seethe deep down inside, finally leading to some health problem. The reverse also happens: extraverts or people who, by virtue of their profession (actors, for example), openly express things of super-significance may be much less expressive in their home life and live to a ripe old age.

Needless to say, there is a very fine line between being reserved and being unsociable, between an easy manner and over-familiarity, and between healthy determination and fanaticism: the pendulum readily slips from one state into the other. Our most precious sense is our sense of proportion, which itself should be tempered with moderation, that is, with moderate moderation.

The concluding question in this chapter is why extreme situations should stimulate some people to show the very best of themselves, whilst crushing and paralysing other people totally. I feel that differences in the stability of our pendulums play at least a small part in this. In some people the pendulums are firmly linked to values, the range of their swing being proportional to the value’s degree of importance; in others, the correspondence is distorted and the pendulums are consequently more unstable. This means they can easily swing off into the zones beyond our conscious control.

From this we can conclude that everyone has their own optimum area, or register of significance, where their actions correspond most fully to their values. The significance something has for you at a given moment is not necessarily proportional to its value. The heart of the matter, perhaps, is that, as experiments have shown, the optimum level of motivation for success (that is, neither too much nor too little interest in succeeding) is generally not the potential maximum level (when success may have become a super signficance). On the contrary, it usually lies somewhere between maximum and average (rather like the golden mean in maths which is so mystically important for harmony in any field: music, art, architecture, the human body, design, etc.), although this varies in different individuals and character types. Thus the apparently logical belief that if you really want to do something you will be able to do it is not true for everyone. On the contrary, as Pushkin perceptively wrote:

«The less we seem to love a woman

The easier to win her heart…»

This is true of life in general and not just in the case of relationships. Sometimes we really need to apply maximum efforts in order to achieve something: we need to be able to want it passionately and to do as much as we possibly can. At other times, however, and this is far more difficult, we need to know when and how to leave well alone in order to achieve our aim: how to conquer by retreating.

This is the theme of the rest of the book. Whatever we are doing (whether we are studying, loving, or working etc.) we are constantly finding new things of significance for ourselves and discarding old ones. This is a fundamental aspect of human nature and a genius may simply be someone who has learnt how to do it to perfection.

Chapter IV

|